Book Review Harlem Voices From the Soul of Black America

… to be a Negro is—is?—

to be a Negro, is. To Be.—from "Toomer," by Elizabeth Alexander

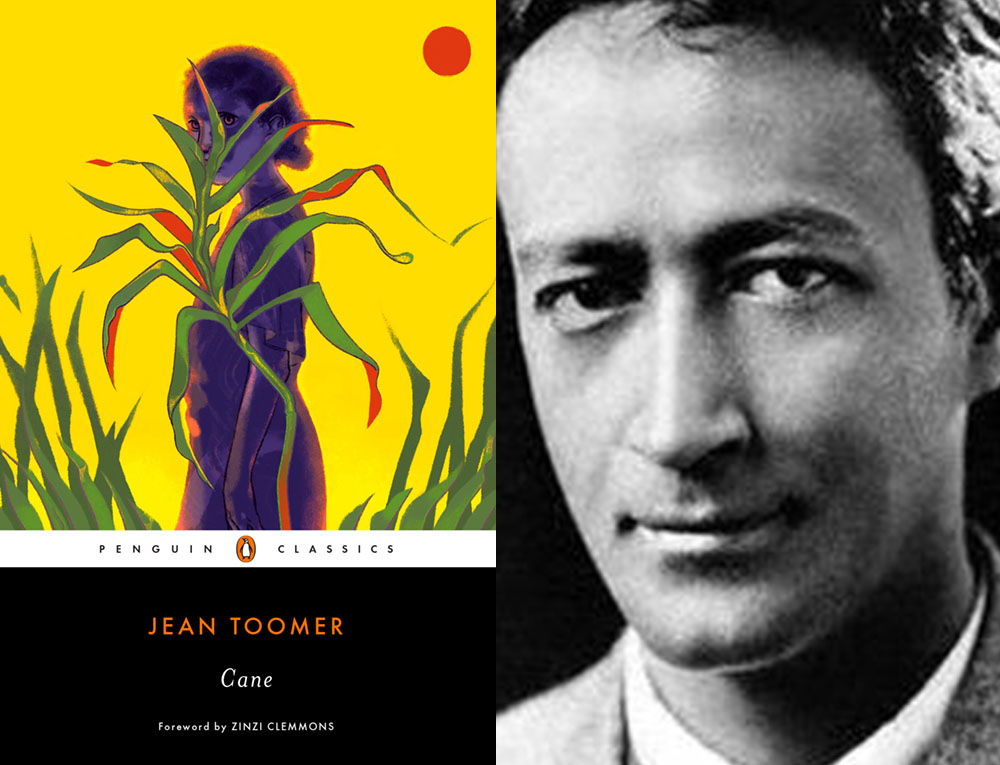

Jean Toomer had a complex relationship to his offset and only major publication, the 1923 volume Pikestaff. The "novel," which Penguin Classics has recently reissued with an introduction by the literary scholar George Hutchinson and a foreword by the novelist Zinzi Clemmons, is a heterogeneous collection of short stories, prose vignettes, and poetry that became an unlikely landmark of Harlem Renaissance literature. Its searching fragments dramatize the disappearance of African-American folk civilisation equally black people migrated out of the agrarian Jim Crow South and into Northern industrial cities. Information technology is a haunting and haunted commemoration of that civilization as information technology was sacrificed to the machine of modernity. Toomer termed the book a "swan song" for the black folk by.

The literary world was and then (as information technology is at present, possibly) hungry for representative black voices; as Hutchinson writes, "Many stressed the 'authenticity' of Toomer's African-Americans and the lyrical voice with which he conjured them into beingness." This act of conjuring lured critics into reflexively accepting the book as a representation of the blackness South—and Toomer every bit the vocalisation of that Southward. As his ane-time friend Waldo Frank remarked in a forward to the volume's original edition, "This book is the South." Pikestaff transformed Toomer into a Negro literary star whose influence would filter down through African-American literary history: his interest in the folk tradition crystallized the Harlem Renaissance's search for a useable Negro past, and would be instructive for after writers from Zora Neale Hurston to Ralph Ellison to Elizabeth Alexander.

For Toomer, notwithstanding, this close identification with blackness folk culture, and the Negro in full general, was inimical to his own self-conception. He largely attempted to evade conventional modes of racial identification. Every bit he pursued a career as a author, the young artist began to clear an idiosyncratic and highly individualistic notion of race wherein he was "American, neither black nor white, rejecting these divisions, accepting people equally people." On official government documents, he would identify alternately as Negro and white. Writing to the Liberator near his racial identity in August of 1922, he declared quite congenially that he possessed "seven blood mixtures," and that because of this, his racial "position in America has been a curious one. I have lived equally amid the 2 race groups. Now white, at present colored. From my own indicate of view I am naturally and inevitably an American. I have striven for a spiritual fusion analogous to the fact of racial intermingling."

In the face up of American laws that protected power by policing arbitrary racial boundaries, Toomer insisted upon a nuanced and unconventional sense of racial identity centered around the reality of racial hybridity—a reality that American law sought to erase. Cane's appearance effaced the writer's hybrid self-conception: executives at the venerable modernist publishing house Boni and Liveright, as well as literary critics, firmly anchored Toomer and his writing to the New Negro movement. Whatsoever Toomer intended to achieve with Pikestaff, the consequence was his conscription into the office of "Negro writer." The friction between Toomer's idiosyncratic race ideology and his publisher'due south conventional race thinking materialized most clearly around Boni and Liveright's attempts to promote Cane equally a Negro text. "My racial composition and my position in the world are realities which I alone may decide," an incensed Toomer wrote to Horace Liveright in 1923. "… I expect and need acceptance of myself on their ground. I do not await to be told what I should consider myself to be."

But Toomer could not override Cane's reception as a primarily Negro text, and the public's perception of him as a Negro writer. Almost immediately after the book's publication, he retreated from the spotlight in search of a philosophical and spiritual course of study that could accommodate his expansive sense of cocky. He eventually vicious under the sway of the Russian mystic George Gurdjieff, whose philosophy figured mankind every bit unable to access a wide consciousness of their essential selves because of an adherence to socially given modes of thought.

Toomer applied Gurdjieff'southward thought to the question of race. Writing in a 1924 fragment that he later delivered as a speech in Harlem, Toomer declared that he sought nada less than the "detaching [of] the essential Negro [private] from the social crust" in order to reach a life that is "witting and dynamic, its processes naturally involving an extension of experience and the uncovering of new materials." In a 1929 journal entry titled "From Place to Identify," he declared his status every bit "a travelled person" whom few people would fault for "a 'home' type of human being, liking a settled habitat. On the reverse, they quickly form the opinion that I am cosmopolitan … [and that] moving about is for me a natural class of life."

As Hutchinson's introduction makes clear, the significant and implications of Toomer'south evasive racial philosophy is even so a subject area of active scholarly interest. In an afterword to Liveright'south 2011 edition of the text Rudolph Byrd and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., reached the conclusion that Jean Toomer intended Cane to function as a "transport out of blackness," and stated that the writer intentionally passed as a white man. In a veiled rejection of that logic, Hutchinson argues that Toomer's ever-shifting presentation of himself was "hardly the act of a black homo attempting to 'pass' every bit white," and agrees with Allyson Hobbs that Toomer was "struggling to convey a holistic understanding" of racial identity for which American racial discourse had no language.

In my heed, the sense of incessant movement that Toomer highlighted in "From Identify to Place" is an essential aspect of this holistic understanding—what he called his "racial position" rather than an identity. Understanding Cane's unique conception of "black" every bit a position of being in or style of moving about the world, equally opposed to a rigid identity, requires an understanding of how highly Toomer valued the pursuit of an elusive movement over deadening stasis. This avoidance of stasis is crucial to grappling with Toomer's ultimately frustrated—and frustrating—intellectual project. Far from being a book that, as Gates and Byrd accept claimed, is intended to transcend black, Cane is the site where Toomer virtually artfully theorizes a surprisingly contemporary notion of what blackness means.

*

Born Nathan Pinchback Toomer in 1894, Jean Toomer came of age in the elite, upper course African-American earth of Washington, D.C. His grandad P.B.S. Pinchback, the fair-skinned son of a wealthy white planter and a mulatto slave, briefly served as acting governor of Louisiana—a tenure that made him the nation's first black governor. In the milieu of the early on twentieth-century black aristocracy, condition was continuous with skin colour; off-white skin afforded Toomer'due south family unit a level of privilege that rendered them somewhat distinct from other African Americans. Later on in his life, Toomer would wistfully depict that milieu every bit unique in the history of American race, a customs "such as never existed before and perhaps never will be once more in America—midway betwixt the white and Negro worlds."

In their 2011 afterword, Gates and Byrd suggest that Toomer intentionally downplayed the extent to which his family was rooted in an African-American cultural world. Still, however romanticized—and, perhaps, disingenuous—Toomer's recollection of this supposedly liminal community was, information technology captured an important truth of his childhood racial experiences. The young Toomer was subject area to a near-constant oscillation betwixt black and white worlds, a movement enabled past the particular privileges that accrued to him as a member of the black aristocracy. After Toomer'southward father, a former slave from Georgia, abandoned the family, Jean was raised in his granddaddy's home in a wealthy white neighborhood of D.C. In accordance with the dictates of D.C.'due south rigorously segregated education organisation, yet, he was educated at the all-black Garnet School. He later lived with his mother in mostly white neighborhoods in New York, merely after her death he returned to D.C.'s blackness elite to alive with an uncle. During his adolescence, he attended the prestigious all-black Paul Laurence Dunbar High Schoolhouse, where his instructors included black luminaries like the historian Carter Thousand. Woodson and the feminist sociologist Anna Julia Cooper.

Toomer somewhen shirked the respectable career expectations attached to someone of his stature in favor of a seemingly aimless wandering. He attended six different colleges, studying everything from fitness to history without e'er earning a degree, until a modest monetary gift from his grandpa enabled him to spend fourth dimension in New York. An aspiring writer, he traversed the modernist cultural worlds of Greenwich Hamlet'south white Lost Generation and Harlem's New Negro motility. Such fluidity was an extension of the immature writer'south early life in D.C.: equally a blanched, racially indeterminate man of mixed racial heritage whose life was characterized by a peripatetic crossing of the color line, Toomer possessed a unique perspective on the American racial bureaucracy as a fundamentally porous and hybrid construction, wherein the black and white worlds interpenetrated one another. It was a construction that individuals could navigate and pass through, at to the lowest degree to the degree that their positions immune such movement.

It's through this prism that Toomer encountered Southern black folk culture. Though the budding writer was firmly rooted in the privileged milieu of Washington'south elite black society, his connection to his Southern heritage was more tenuous. That changed in the fall of 1921, when he accepted a short-term job at Sparta Agricultural and Industrial Institute, a school near Sparta, Georgia. His formative encounters with the black folk culture there would lead him to a new conception of his racial identity. Writing to Sherwood Anderson virtually his experiences in Sparta, Toomer recalled an meet. "Here were Negroes and their singing," he wrote. "I had never heard the spirituals and work songs. They were like a part of me. At times, I identified with my whole sense so intensely that I lost my own identity."

Toomer'southward clarification of his encounter is fascinating in part because it is so bizarrely articulated: I identified with my whole sense so intensely that I lost my ain identity. The repetition of identity catches my attention hither; I take Toomer to mean that he encountered blackness with such strength of perception that the thing of identity passed out of relevance for him. In this light, far from providing Toomer a simple sense of heritage or ancestry from which to write, the South provided him a space and linguistic communication in which to elaborate his unstable sense of race. In the letter of the alphabet to Anderson, his description of the come across with the spiritual does not model a simple procedure of identification. Rather the discovery of a black cultural inheritance in his own person exposes Toomer to an "identity" that is, paradoxically, the effacement, loss, and evasion of stable identity. This interface with blackness folk civilisation seems similar to what we take come up to call fugitivity in contemporary parlance: an functioning of perpetual evasion that transforms any attempt to formulate blackness into an countless elaboration of its possible iterations. This evasiveness, equally the poet and critic Fred Moten has said, tends towards a want to "call up from no standpoint … to retrieve exterior the desire for a standpoint …"

When ane knows to look, one recognizes that this sense of perpetual evasion, this straining toward an "outside" to conventional race ideology, exists throughout Cane. It is this want to oscillate betwixt positions that animates Pikestaff's conception of blackness. Indeed, the book posits oscillation every bit blackness' operative quality. While Cane is often described as an attempt to capture and preserve a dying black folk civilisation, information technology might be more authentic to describe it as a book that takes such fleetingness every bit that culture'south primary characteristic, and which seeks a formal representation of blackness' protean impulses.

This is virtually evident in Cane's formal qualities, in the fashion it insists on gathering various short stories, poems and even phase drama beneath the rubric of "novel," using heterogeneity to forcibly alter a genre category. The book's terminal piece, a semi-autobiographical curt story titled "Kabnis," tells the story of the eponymous narrator's frustrating stint education at a school in rural Georgia. Stymied and frustrated by a customs that is smothered in inherited assumptions about what defines black, Kabnis revolts. Those assumptions "won't fit int th mold thats branded on m soul," he declares. "Thursday form thats burned int my soul is some twisted atrocious affair that crept in from a dream, a godam nightmare, an wont stay still unless I feed information technology. An it lives on words." This notion of a misshapen, awful class that defies conventional expression haunts Kabnis; his challenge is to find words that might express what is inside. The story models that drive toward "Misshapen, divide-gut, tortured, twisted words" via its form: the piece is a bizarre conflation of the short story and stage drama forms, one that largely eschews the lyricism for which Pikestaff was so popular in favor of a gnomic attribute whose obscurity arises from the divergent formal qualities information technology pulls together. W.E.B. Du Bois fumed most this mercurial quality, wishing that Cane were a text he could "empathise instead of vaguely guess at."

Toomer's accent on the heterogeneity at the heart of blackness is nowhere as clear as it is in "Vocal of the Son," the verse form that might be Cane's most famous piece. With language that explicitly nods toward the tragedy of a fleeting folk culture, the poem lends itself hands to interpretation as an elegy for the decease of an authentic black culture. The poem's speaker mourns: "In fourth dimension, for though the sun is setting on / A song-lit race of slaves, information technology has not set; / Though tardily, O soil, it is not too late nonetheless / To catch thy plaintive soul, leaving, soon gone, / Leaving, to catch thy plaintive soul soon gone." This swan song is not merely the occasion for mourning, however; soon, the speaker turns to address his ancestors directly. "O Negro slaves, dark purple ripened plums," he begins. "Squeezed, and bursting in the pine-wood air / Passing, before they stripped the old tree bare / I plum was saved for me, 1 seed becomes / An everlasting song, a singing tree / Caroling softly souls of slavery / What they were, and that they are to me / Caroling softly souls of slavery."

At that place's a kind of divergence happening hither, an acknowledgement that in trying to capture and preserve his heritage, the poem's speaker is simultaneously transforming it. In the poem, preservation is inescapably tied up in a vehement process of stripping, of forcible alteration, whereby the speaker lifts a unmarried seed from the wholeness of folk civilization. In extracting that seed from the former tree, the speaker might become the flagman to a song of departed black slaves—but he likewise draws a distinction betwixt who the slaves actually were and what they get as he subjects them to representation. Withal, somehow, this deviation between history and artistic representation is united in a single, everlasting song—the black folk song that appears every bit a perennial expression of an unchanging racial culture, but really obscures a persistent mutability.

In this fashion, Toomer presents blackness as an backlog that vexes every endeavor to restrain it. He figured blackness as a perpetual becoming, something that but "is," every bit the poet Elizabeth Alexander would later on suggest in the poem "Toomer." In place of narrow identity, he proffered an itinerant and changeable movement that refuses conventional notions of identity, insofar as it is nothing more "an capricious figure of a Negro, equanimous of what another would have him be similar." To him, this instability was the blackness that American racial politics took pains to avoid acknowledging. In this sense, Cane represents 1 of the beginning attempts to chant, every bit Moten has formulated, an "open set up of sentences of the kind black is x …" While Toomer might have (quite ironically) struggled for the rest of his career to observe a mode of expression in which to communicate such radical instability, Cane's reappearance gives us the adventure to recognize his inexpressible ideal as a step toward theorizing the mode of ceaseless predication we've come to know as "blackness study."

Ismail Muhammad is a author and critic living in Oakland, where he's a staff writer for the Millionsand contributing editor atZYZZYVA. His writing has appeared inSlate, the Los Angeles Review of Books, New Republic, The Nation, and other publications. He'south currently working on a novel nearly the Neat Migration and queer archives of black history.

Source: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/01/14/how-jean-toomer-rejected-the-black-white-binary/

0 Response to "Book Review Harlem Voices From the Soul of Black America"

Post a Comment